Rules don’t shrink you — they widen the road.

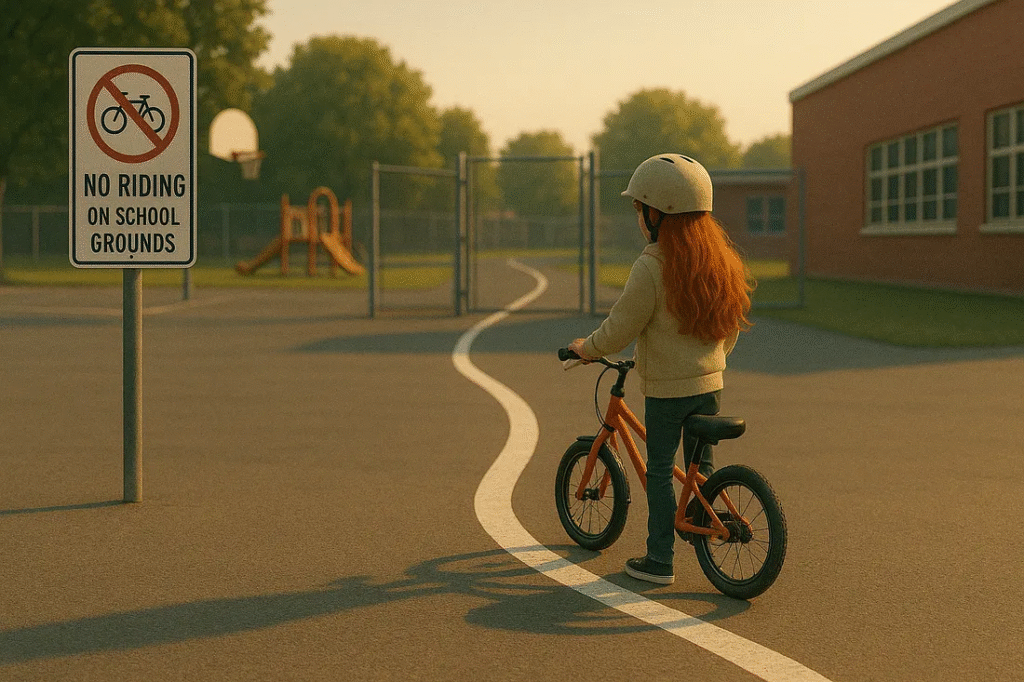

Just a kid on her bike.

Just a dad jogging next to her, trying to act like he wasn’t dying.

“I want to get better at shooting a basketball,” she said. “We play every day in P.E.” She was seven.

It was a lazy Saturday in 1992. Back when phones had cords and I still thought caffeine-free soda should be illegal.

We headed to the school playground. She hopped off her bike before we even hit the blacktop.

“Whatcha doin’, sweetheart? We’re not there yet.”

She stopped cold. Looked me dead in the eye. “We’re not allowed to ride bikes on school grounds.”

“It’s Saturday,” I said. “Rules don’t apply on weekends.”

“No, Daddy. It’s not right.”

She was all righteousness… fresh off training wheels. So we walked the bike.

I didn’t tell her the truth: that I had just come out of the tail end of my first manic episode and hadn’t followed a rule since parachute pants were in style. At that point, I had no real rules of my own — unless you count “Don’t run out of vodka before the liquor store closes.”

Back then, I was a little frustrated with her little-kid honesty. Today, I envy it.

When breaking rules doesn’t break the sky

By middle school, I had figured out something dangerous: you can break a rule and the sky doesn’t fall. That idea lit a fuse that exploded into consequences I’d spend two decades chasing down with vodka and denial. At 28, I tried to stop. For the next 14 years it was relapse, rinse, repeat. There came mental issues when there was no alcohol to keep symptoms at bay. Then psych meds with warning labels longer than my attention span.

Twenty years of drinking like it was my full-time job.

Fourteen years trying to get sober.

Spoiler alert: I wasn’t a quick study.

Tried 12-step recovery. Heard them say: “We don’t have rules. Just suggestions.”

Cool. So, I suggested I do whatever I wanted.

Sprinkle in some bipolar mania, full-blown psychosis, and a lifestyle with less structure than a wet napkin — and yeah, recovery stayed out of reach.

I floundered. Rudderless.

Skyy vodka was the sea. I was the ever-present shipwreck.

The parking-lot pivot

Then came a parking lot outside of a 12-step meeting.

A meeting I didn’t want to be at.

A man with a calm voice and tired eyes who told me how he finally broke his own relapse cycle.

The secret? He stopped treating the 12 steps like inspirational bumper stickers and started treating them like laws of physics.

Do this — or fall apart.

That man became my sponsor. Really, my mentor.

And for the first time, I stopped sponsoring myself — because myself had a long track record of leading me straight to hell with a bottle in hand and a smirk on my face.

Science break: Why rules make you freer

Structure feeds freedom. In Self-Determination Theory, autonomy isn’t “anything goes.” It’s choosing constraints that align with your values so your life stops whiplashing you. Rules are pre-decisions. Make the call before the craving shows up and you’ve already lifted half the load. Psych calls this an implementation intention: If X happens, I do Y. That tiny script trims decision fatigue, protects working memory, and keeps your brain from sprinting into chaos.

Relapse science backs it. In Marlatt’s model, high-risk situations trigger one of two paths: coping or collapse. Rules make coping automatic. Pre-commitment (think Odysseus tying himself to the mast) beats white-knuckle willpower. Rehearsed often enough, rules become habits … the brain files them under “easy.” Predictable routines calm dopamine’s jitter, reduce noise, and give you traction. That’s freedom with a steering wheel.

What I learned the hard way

Without rules, I’m not free.

Without rules, I’m not edgy or enlightened or living my truth. I just thought I was.

Without rules, I’m a prisoner. I find myself chained up by my own impulses and addictions. That ever-present voice in my head telling me I’m never gonna make it.

Freedom isn’t doing whatever you want.

Freedom is building a life so solid you don’t want to tear it down every time your brain gets itchy.

Now, don’t get it twisted. I ain’t out here preaching sainthood. I break my own rules more often than my little Yorkie breaks into the snack drawer — which, for the record, he’s somehow rigged open with a rubber band, a laundry clip, and what I’m pretty sure is a tiny shank made from a toothpick. Dude’s got hustle. And honestly? So do I — just not always in the right direction. But I’ve learned this: when I screw up, I don’t duck and hide anymore. I don’t ghost myself or pretend I didn’t see it coming. I write about it because honesty heals. And shame? Shame can’t thrive in the light.

Why this blog exists

Recovery Rules was born from the ashes of an older blog, ADoubleShotofRecovery.com. That name fit me for a while — recovering from booze and from bipolar. But these days, I’m done pretending those parts of me are separate. I no longer treat them separately.

I’m dual-diagnosed.

That’s not a punchline or a pity party. It’s a fact. And I’ve thrived in spite of it.

This blog is for the tinfoil-hat crowd. Though I went back to college for a master’s in counseling and a PhD in psych, I’m one of you. The ones who hear voices, cry in parking lots, and drink or drug not because it’s fun, but because the alternative feels unbearable.

It’s for anyone battling both addiction and mental illness — and trying like hell to not let either win.

Here, I’ll share what’s worked for me and how I still mess it up. I’ll lay out the rules I try to live by.

I’ll share about how a stint in that mental health laboratory known as prison honed my skills as a therapist and transformed me into a mentor. Peer level. Been there, done that.

Rules.

You don’t have to follow them. Hell, I don’t always follow them. But they work. I only write about what I’ve tried.

Rules — the right rules — can keep the chaos at bay.

Can keep you out of the ER, out of jail, out of your own damn way.

So if you’re looking for detached clinical advice, go find a white coat.

If you want real talk, some raw truth, and the occasional metaphor involving Yorkie snack drawers or — preparing you for what’s coming — peeing with no toilet in sight, you’re in the right place.

Just know this: you’re not alone. And you’re not broken beyond repair. Though no longer a clinician (by choice), I know the science behind what works. I’ve studied it, taught it, and, most importantly, lived it.

We’re not from the land of broken toys. We just need some rules that actually work. Oh, and obvious play on words: Recovery does Rule.

Call to Action

Pick one rule — just one — and run it for seven days.

Write it down, tell one person, and when your brain itches, follow the rule anyway. Then come back, drop a comment, and subscribe or follow so we can keep building a life that doesn’t fall apart on Tuesdays.

References (select)

Ariely, D., & Wertenbroch, K. (2002). Procrastination, deadlines, and performance: Self-control by precommitment. Psychological Science, 13(3), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00441

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(7), 493–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 38, pp. 69–119). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1

Marlatt, G. A., & Donovan, D. M. (Eds.). (2005). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Thaler, R. H., & Shefrin, H. M. (1981). An economic theory of self-control. Journal of Political Economy, 89(2), 392–406. https://doi.org/10.1086/260971

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit–goal interface. Psychological Review, 114(4), 843–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.843

Wood, W., & Rünger, D. (2016). Psychology of habit. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

Schultz, W., Dayan, P., & Montague, P. R. (1997). A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science, 275(5306), 1593–1599. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.275.5306.1593

Witkiewitz, K., & Marlatt, G. A. (2004). Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: That was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist, 59(4), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224